The Organizational for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD) is trying to hold multinational corporations to appropriately high standards of corporate social responsibility. OECD member states include thirty of the major economies of the world. Ten years ago, they adopted guidelines regarding human rights, environmental protection, the rights of workers and child protection. Now they are in the throes of a ten year review. Every member country has appointed an NCP -- a National Contact Point -- to investigate claims that multinational corporations headquartered in their country, or their subsidiaries wherever they might be located, have violated the guidelines. The NCPs have investigated as best they can (often with very limited staff and budget). The assumption is that being called out by a national government will push multinationals to correct whatever guideline infractions they or their subsidiaries may have committed. Unfortunately, it has been hard for the NCPs to complete many of the needed investigations, particularly those filed by unions or NGOs in far off corners of the world. On some occasions, NCPs have not found sufficient evidence that the guidelines have been violated, but there are clearly circumstances that needed attention. At a recent meeting of all the NCPs and some of their constituent organizations (including their Trade Union Advisory Group, their Business and Industry Advisory Group, and OECDWatch) the NCPs were reminded that their goal should be to rectify inappropriate practices, not just determine whether the guidelines have been violated. More generally, the NCPs were urged to step back from their adjudicatory (or investigatory) efforts and build their problem-solving capabilities. In particular, they were urged to take their mediation mandate seriously.

Thursday, July 8, 2010

Mediation As Problem-Solving

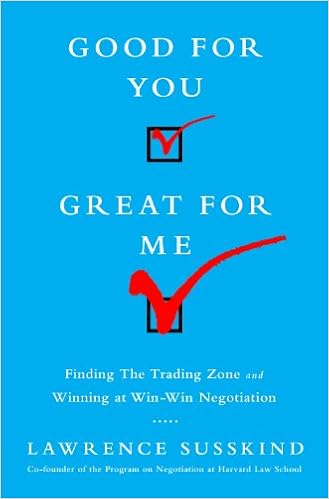

Posted by Lawrence Susskind at 6:12 AM 1 comments

Labels: child protection, environmental protection, human rights, mediation as problem-solving, OECD, rights of trade unions

Friday, December 4, 2009

Resolving Complaints About Irresponsible Corporations

Corporations are supposed to pay attention to environmental, health, safety, labor, tax, consumer protection, information disclosure, and human rights laws wherever they set up shop. But, we've all seen and heard stories about multinationals guilty of violations in far-away places. They have been charged with allowing unsafe working conditions, blocking legitimate unionization efforts; ignoring environmental and health standards, bribing officials, and turning a blind eye to human rights violations. Developing countries are often ambivalent about holding violators to account: they can't afford to lose the investments and the jobs, and they often lack enforcement muscle even if they want to act.

Posted by Lawrence Susskind at 3:23 AM 1 comments

Labels: corporate social responsibility; mediating CSR complaints; roles and responsibilities of intermediaries, OECD